What if Hillary Clinton had become president?

মানিকগঞ্জ বার্তা

প্রকাশিত: ২৬ মে ২০২০

The novel Rodham imagines a near-real world where everything is different. Can fantasy fictions help us create a ‘better future’ asks Caryn James.

In 2016, the US came so close to electing Hillary Clinton president, and Britain came so close to rejecting Brexit. What if things had gone differently? Creators of some of the best recent novels and television shows are creating alternate worlds based on those tantalising what-ifs. Curtis Sittenfeld’s audacious new novel, Rodham, imagines what Hillary Rodham's life would have been like if she had not married Bill Clinton. (Hint: her political ambitions kick in earlier.) Sci-fi master William Gibson's novel Agency is set partly in a world where Hillary is president and Brexit never happened. This season’s first instalment of the smart, politically-charged legal drama The Good Fight (on CBS All Access) is set during a Hillary Clinton presidency. That turned out to be a character’s dream, but it was nice while it lasted.

More like this:

- How dark stories can comfort us

- The prophetic writer who gave us hope

Other new counterfactual worlds have a feminist slant, too. The underappreciated AppleTV+ series For All Mankind imagines what would have happened if the Russians had put a man and then a woman on the moon before the US. Suddenly President Richard Nixon, not known to care about women’s rights, demands that the US does the same. And no feminist fantasy is more trenchant than Margaret Atwood’s latest novel, The Testaments. A sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, it takes us towards the downfall of the anti-woman state of Gilead.

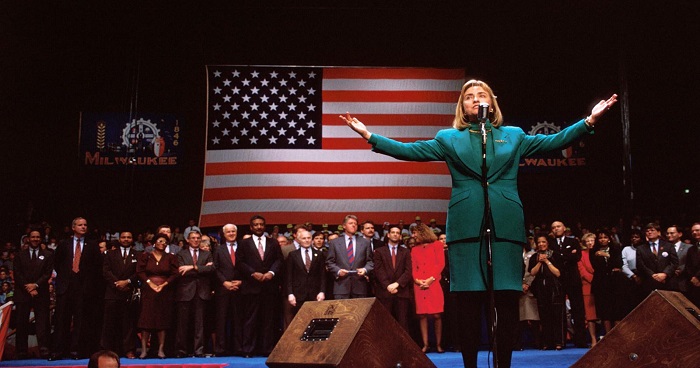

The novel explores how Hillary Rodham’s career might have gone if she hadn’t married Bill Clinton (Credit: Getty)

Readers and viewers may be tiring of familiar dystopian fictions, especially since they have blurred into reality. These new works replace them with hopeful fantasies, solidly rooted in the real world. It is a coincidence of timing they are landing in the midst of a global pandemic, but these counterfactual stories are potent reminders of how different today might have been.

Until now, alternate histories have most often been cautionary tales about a bleak, authoritarian future, with World War Two a flashpoint. In HBO’s The Plot Against America, Charles Lindbergh is the fascist president of the US. In the Amazon series Hunters, Al Pacino’s character leads Jewish Americans as they track down resurgent Nazis in the 1970s. And Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle posits that Germany and Japan won the war. These series function as warnings about our own political dangers.

But 2016 sparked a different dynamic, perhaps because a non-Brexit world and a President Hillary Clinton were such near-misses, the results so shocking. It may be a stretch to imagine that the Nazis triumphed, but we had already imagined a Brexit defeat and a Clinton victory, bringing these alternate histories close to home.

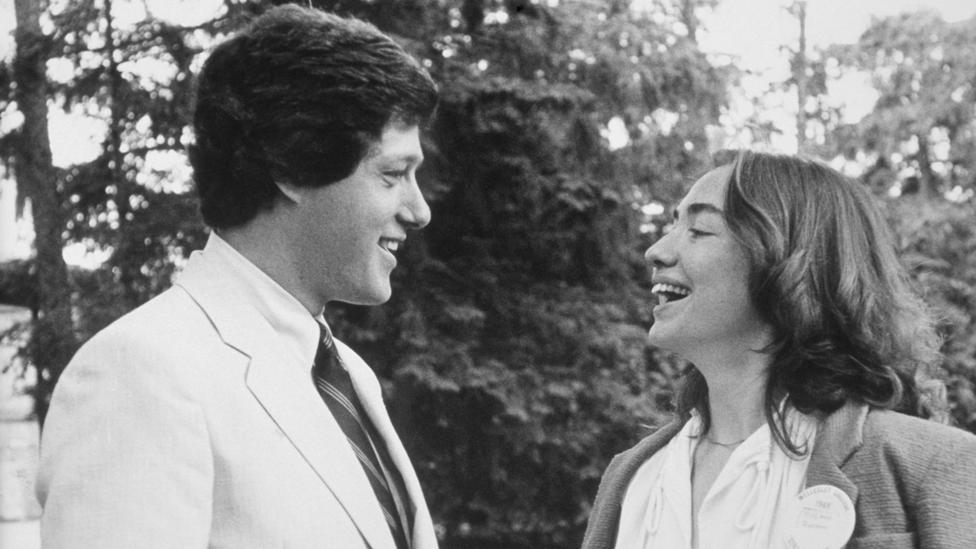

Sittenfeld’s novel is the most daring, as it takes us inside a fictional Hillary’s mind and uses a first-person voice. Getting inside a living person’s head sounds like a colossally bad idea, but Sittenfeld makes it convincing here, just as she did with a character based on First Lady Laura Bush in her 2008 novel, American Wife. The first stretch of Rodham rarely diverges from Clinton’s life, while creating a psychologically astute portrait that seems as authentic and revealing as any non-fiction biography. Fiction gives us an intimacy that a factual portrait couldn’t, though. When Hillary and Bill meet as idealistic students at Yale Law School, we feel their genuine mutual attraction, sexually and intellectually, in what the fictional Hillary calls a “swoony” romance. Bill is not the most faithful or honest guy around, but we understand why she follows him to start a life together in Arkansas, where his political career begins.

The TV series For All Mankind imagines an alternative, female-friendly history of the space race (Credit: AppleTV+)

That’s where the novel swerves. It doesn’t spoil much to reveal that the alt-Hillary loses faith in Bill’s character, moves to Illinois and begins a stellar political career of her own. Even then, Sittenfeld shrewdly relies on real-life details, slightly skewed. “I suppose I could have stayed home, baked cookies, and had teas,” her Hillary says during a campaign interview, repurposing the baking-cookies line that created a backlash for the real Clinton. Her political enemies in the novel chant “Shut her up” at her rallies, a counterpart of the “Lock her up” cry at actual Trump rallies. As in the best alternate histories, this is entirely believable. Sittenfeld includes just one, droll, outsized fantasy. Donald Trump appears in the novel, not as a presidential candidate but as a relatively harmless buffoon.

Gibson creates a similar political shadow world in Agency, set in two fictional timelines. One strand of the story is set in post-apocalyptic London in the 22nd Century, where people create so-called “stubs”, alternate realities. The other strand takes place in a stub in San Francisco in 2017, when the Brexit vote and the previous year’s presidential election turned out differently due to “reduction in Russian manipulation of social media”. True to its sci-fi genre, Agency is primarily about artificial intelligence, and a young woman named Verity who is testing a new AI app in 2017. But for non-sci-fi fans, the social and political backdrop is its most intriguing aspect.

Gibson's fiction now offers a clear-sighted reminder that plenty of scientists could see a disaster coming

Gibson’s 22nd-Century characters regard the alternate election and Brexit results as “positive change”, and no wonder. In their own time, Parliament no longer exists and they have endured pandemics that the 2017 characters have not encountered (at least not yet). Published in January, Agency was obviously written before a pandemic was part of our daily lives. Gibson's fiction now offers a clear-sighted reminder that plenty of scientists could see a disaster coming. Hillary Clinton is not named in Agency, but the female president is obviously her, down to the “Lock her up” graffiti in a toilet cubicle. Verity recalls a debate in which the president’s opposing candidate “loomed behind her”, and remembers “her own sickened disbelief at his body language... his deliberate violation of his opponent’s political space”. Verity’s memory could well be an account of the actual Trump-Clinton debate a month before the election.

An episode of the legal drama The Good Fight is set during an imaginary Hillary presidency (Credit: CBS All Access)

These near-real fantasies do not replace dystopias with utopias, but with better versions of the present. Agency’s fictional president can’t restore peace in the Middle East. It’s enough that she averts one near disaster there. There is not even a utopia in the dream of the Hillary-supporting, Trump-hating attorney, Diane (Christine Baranski) in The Good Fight. In her imaginary Clinton administration, cancer is cured. Yet because Trump was not elected there was no Women’s March in protest, and no #MeToo movement.

Butterfly effect

For All Mankind goes even further in depicting the Butterfly Effect, the tradeoffs that can happen when an improved history is substituted for factual events. The series is an ambitious vision of space exploration, with dramatic moon landings. It is also an absorbing personal melodrama in which characters based on historical figures exist along with fictional astronauts. It feels as realistic as anything in purely fact-based films, like the Neil Armstrong biopic First Man.

Much of the plot in the ironically titled For All Mankind concerns the fictional American women who first go into space, in the early 1970s, a decade before that actually happened. But the show emphasizes the difficulties behind their accomplishments. The trade-offs are worth it, but the women struggle with competitiveness, insecurity, and the toll on their relationships, not to mention rampant sexism. In this alt-world, Nixon loses his reelection campaign and Ted Kennedy becomes president. But as in The Good Fight, the better presidency does not go smoothly. And the series is haunted by deaths, some due to space accidents, and some just life on Earth.

Margaret Atwood followed up The Handmaid’s Tale with The Testaments (Credit: Hulu/MGM)

A key work in this broader feminist pattern was The Testaments, published last autumn. Atwood is just the artist to replace dystopian ideas with more hopeful signs. After all, she created one of the most chilling dystopias ever in The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. The Republic of Gilead, with handmaids used as sexual slaves and baby factories for commanders, was more ominous than ever by the time it became a Hulu series in 2017, when women’s rights were increasingly under attack. Atwood’s vision is still so disturbing, it hardly registers that the book’s epilogue, set in 2195, reveals Gilead to be an artifact from the past.

It’s all the more persuasive, then, that she offers a glimmer of optimism in The Testaments, with a trajectory moving from darkness to light. The main action is set 15 years after the first novel, with Gilead on the cusp of falling. The novel’s three narrators include the horrendous Aunt Lydia, a willing tool of the oppressive male leaders. She is secretly writing an account of her past, full of regrets, and is plotting to help the other two narrators – young women, one raised in Gilead and the other part of its Mayday resistance – escape to Canada with evidence of Gilead’s crimes and corruption.

Lydia now realises how Gilead became possible. She and the rest of the population ignored signs of a crumbling climate and society. We should have paid attention, she says, to “the floods, the fires, the tornadoes, the hurricanes... the tanking economy, the joblessness”. How familiar is that? In recognising the danger that comes from obliviousness, Atwood points us toward a better future, earned through the ordeals her characters have weathered.

These fictions deliver welcome scenarios for this moment

Being optimistic is not nearly enough, though. Ryan Murphy’s Netflix series Hollywood, which imagines what might have happened if the movie industry had overcome all its racist, homophobic, sexist biases back in the 1940s, could be a case study in how not to create an alternate history. The glamorous series is compulsively watchable, even with its howlingly bad dialogue and over-the-top acting. But awfulness may be the least of its problems.

It glibly reconstructs a past in which a black woman stars in a hit movie and wins an Oscar. The movie’s gay, black screenwriter wins one too. So does its Asian-American director. It’s as if Murphy waved a magic wand, and any roadblocks based on race or gender disappeared. Hollywood is all about fantasies, but this one has less connection to reality than any fairy tale, where the heroes have to struggle to overcome obstacles.

Can alternate histories such as For All Mankind help us understand our past – and so imagine a better future? (Credit: AppleTV+)

The bold new alternate histories are not suggesting that we can time travel backwards and prevent a virus, eliminate bias, or reverse the Brexit fallout. Wernher von Braun, the real-life scientist, says in a fictional scene in For All Mankind, “Every political system is flawed and every bureaucracy is corrupt”. These fictions embrace such hard-nosed realism. They also deliver welcome scenarios for this moment. If we can imagine a different past, flawed though it may be, we are that much closer to creating a better future.

- আশ্রয় নেওয়া মিয়ানমারের ২৮৮ বিজিপি-সেনাকে হস্তান্তর

- ৩ দিনের ‘হিট অ্যালার্ট’ জারি

- হিট স্ট্রোকে এসএসসি পরীক্ষার্থীর মৃত্যু

- কারাগারে অসুস্থ হয়ে হাজতির মৃত্যু

- স্ত্রীকে কু*পি*য়ে জ*খ*ম করল পাষণ্ড স্বামী

- গরমেও চলছে স্কুল-কলেজ-মাদ্রাসা!

- দায়ীদের বিচার না হওয়ায় ক্ষোভ

- দুই দিনে দুই মাদরাসাছাত্র নিখোঁজ

- খাদে পড়ে ৬ শ্রমিক নিহত

- বুবলির নায়ক সিয়াম

- প্রাবোওকে পরবর্তী প্রেসিডেন্ট ঘোষণা করল ইন্দোনেশিয়া

- একই গাড়ির চাপায় চালক ও সহকারীর মৃত্যু

- কারাভোগ শেষে ১৭৩ বাংলাদেশি কক্সবাজারে

- প্রধানমন্ত্রী ব্যাংকক পৌঁছেছেন

- নিহত শ্রমিকদের প্রতি শ্রদ্ধা

- তৈফিক ইমরোজ খালিদীর বিরুদ্ধে দুদকের চার্জশিট

- এখনো শেষ হয়নি তিন মামলার বিচার

- দেশে ফিরবেন সেই ২৩ নাবিক

- ইসরায়েলের ‘কিছুই অবশিষ্ট থাকবে না’

- জিবুতিতে ফের অভিবাসীদের নৌকাডুবি

- যাত্রা শুরু হলো মারামারি দিয়ে

- বাংলাবান্ধা স্থলবন্দরে ৩ দিন আমদানি-রপ্তানি বন্ধ থাকবে

- বুধবার গ্যাস থাকবে না ১২ ঘণ্টা

- স্ত্রীকে কুপিয়ে হত্যা, স্বামী গ্রেফতার

- ভরিতে কমল ৩১৩৮ টাকা

- কারিগরি শিক্ষা বোর্ডের চেয়ারম্যানকে অব্যাহতি

- চতুর্থ ধাপের তফসিল হতে পারে আজ

- বিদ্যুৎ উৎপাদনে নতুন রেকর্ড

- স্টুডিওতে আ*গু*ন

- মেট্রোরেলের আগারগাঁও-মতিঝিল অংশের উদ্বোধন ৪ নভেম্বর

- প্রাবোওকে পরবর্তী প্রেসিডেন্ট ঘোষণা করল ইন্দোনেশিয়া

- একই গাড়ির চাপায় চালক ও সহকারীর মৃত্যু

- তৈফিক ইমরোজ খালিদীর বিরুদ্ধে দুদকের চার্জশিট

- স্ত্রীকে কু*পি*য়ে জ*খ*ম করল পাষণ্ড স্বামী

- বাংলাবান্ধা স্থলবন্দরে ৩ দিন আমদানি-রপ্তানি বন্ধ থাকবে

- কারাভোগ শেষে ১৭৩ বাংলাদেশি কক্সবাজারে

- স্ত্রীকে কুপিয়ে হত্যা, স্বামী গ্রেফতার

- বুধবার গ্যাস থাকবে না ১২ ঘণ্টা

- প্রধানমন্ত্রী ব্যাংকক পৌঁছেছেন

- দেশে ফিরবেন সেই ২৩ নাবিক

- দায়ীদের বিচার না হওয়ায় ক্ষোভ

- ইসরায়েলের ‘কিছুই অবশিষ্ট থাকবে না’

- এখনো শেষ হয়নি তিন মামলার বিচার

- দুই দিনে দুই মাদরাসাছাত্র নিখোঁজ

- খাদে পড়ে ৬ শ্রমিক নিহত

- জিবুতিতে ফের অভিবাসীদের নৌকাডুবি

- গরমেও চলছে স্কুল-কলেজ-মাদ্রাসা!

- যাত্রা শুরু হলো মারামারি দিয়ে

- বুবলির নায়ক সিয়াম

- নিহত শ্রমিকদের প্রতি শ্রদ্ধা